by Shiri Ourian

Executive Director

American Friends of the Parents Circle

March 10, 2025

I spent a week in South Africa with the Parents Circle’s partner organization, TELOS, listening and learning, processing and grappling, uncovering and bearing witness. My intent was clear—to return with insights from South Africa to inform my leadership of American Friends of the Parents Circle.

Instead, I returned with more questions than answers.

South Africa, a land of breathtaking beauty and unbearable pain, is both a warning and an inspiration. Its history of oppression and resistance, its fragile yet powerful attempts at healing, and its ongoing struggles challenge easy conclusions. What follows are the questions shaping my thinking as I return.

1. What Makes Us Human?

Our journey began at the Cradle of Humankind, a UNESCO World Heritage Site outside Johannesburg, where fossils continue to reveal the origins of life. As we stood in the place where our earliest ancestors walked, the question seemed to ask itself: What makes us human?

At the Cradle, the likeness of humankind is undeniable. Our commonalities stretch back millions of years. And yet, somewhere along the way, we decided differences mattered more. When did we begin drawing lines, defining us and them, assigning greater worth to some and lesser worth to others? And once drawn, how do we erase those lines?

2. How Will We Achieve Peace Without a “Mandela”?

Nelson Mandela’s leadership was not incidental to South Africa’s path forward—it was foundational. His moral clarity, vision, and ability to lead people through pain and fear toward hope made the unimaginable possible.

And yet, I look around today, and I do not see a “Mandela”. Not in Israel. Not in Palestine. Not in America.

I recognize that this may not be due to a lack of extraordinary Palestinian and Israeli leaders. So many Palestinians who have sought to lead are imprisoned or killed. Courageous Israeli voices are too often dismissed as traitorous, victims of a political system that rewards fear over reconciliation. The absence of a single, visible leader is not a reflection of absence in spirit or effort—it is the result of structural barriers designed to suppress and remove leadership that challenges the status quo.

Perhaps we are nurturing a Mandela as we speak, somewhere in the Parents Circle’s Young Ambassadors for Peace program. Perhaps change does not begin with a single leader, but with the slow, patient work of raising a generation of peacemakers who will recognize one another when the time comes. But still, I wonder: Can reconciliation take hold without a singular figure to guide it?

3. Is Violence a Necessary Precursor to Peace?

Due to an illness that sidelined me for a day, I was unable to visit Soweto, the township at the heart of the struggle against apartheid. But I studied the Soweto Uprising—a student-led protest in 1976 against the imposition of Afrikaans as the primary language of instruction in Black schools. The uprising officially claimed 176 lives, though estimates are much higher. The famous photograph by Sam Nzima of 12-year-old Hector Pieterson being carried after being shot became an international symbol of apartheid’s brutality.

My colleagues shared that they were joined that day in Soweto by Antoinette Sithole (Hector Pieterson’s sister) and also Seth Mazibuko, the youngest student protestor who spent 18 months in solitary confinement and then 7 years on Robben Island. Both had very different views on reconciliation in response to the same horrific experiences.

Soweto’s resistance helped bring apartheid to the world’s attention and, ultimately, to its knees. And yet, as someone who has never directly lost a loved one to war or a political struggle, I ask this question with humility: Is violence a necessary precursor to peace? Must there always be blood before healing?

4. What Are Our Blind Spots?

One of the visits I most anticipated was to the The Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation in Cape Town, dedicated to preserving the legacy of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). I had so many questions about the TRC process—how it is viewed today, what it got right, and where it failed.

A burst pipe prevented our visit, but we met Janet Jobson, its CEO, whose insights left a lasting impression. She spoke of South Africa’s journey toward healing—of reconciliation, repair, and reimagination. She described reconciliation as “finding each other”, a phrase so simple yet profound that it has stayed with me.

She emphasized self-repair as a prerequisite for societal repair. And yet, she lamented how the South African government ultimately failed to implement many TRC recommendations—over 300 cases were referred for prosecution, and only one was pursued.

As we spoke, I introduced myself and shared the work of the Parents Circle, explaining how bereaved Israelis and Palestinians build reconciliation through personal storytelling and dialogue. She nodded, listening intently. Then she asked a question that caught me off guard:

“Why is there no Israeli counter-movement to support peace?”

I looked at her, momentarily stunned. This intelligent, well-informed woman was unaware of the robust Israeli peace movement and the many people-to-people organizations.

I wondered: Are we not doing enough? Is the Israeli peace movement failing to reach those who should be its natural allies? Or was this simply her blind spot? And if so, what are mine?

Identifying blind spots is essential—because what we fail to see, we fail to address. Reconciliation requires confronting not only the truths we are comfortable with but also those we have overlooked, dismissed, or never thought to question.

5. Can We Reimagine a Different Future?

One theme that emerged repeatedly during this trip was the power—and necessity—of reimagination. Both Janet Jobson and Lwando Xaso, a constitutional lawyer who walked us through the drafting of South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution by visionaries like Albie Sachs, spoke about reimagination as essential to reconciliation

The architects of South Africa’s transition did not simply dismantle apartheid; they worked to reimagine a new society—one built on justice, inclusion, and human dignity. Reconciliation was not framed as looking back to settle past injustices, but as looking forward—toward a world that had not yet been created but could be.

One of the most visceral moments came when we met Rene August, a veteran of the anti-apartheid movement and an Anglican priest who now works as a reconciliation trainer. She led us through a colonial-era castle, once used for the slave trade, torture, and oppressive decrees that shaped South Africa’s history. As we walked its corridors, we read aloud a document acknowledging, recognizing, and mourning those who had suffered there before us.

But the exercise did not end with grief. It was about reimagination. Standing in a place steeped in pain, we were invited to envision something new: a world not built on power and oppression, but on wisdom, forgiveness, humility, and humanity.

It was a moment that will stay with me.

Reconciliation is not simply about confronting the past—it is about expanding the boundaries of what is possible. It is an act of radical imagination, of daring to see a future that does not yet exist and working to bring it to life.

And so I ask: Are we doing enough to reimagine?

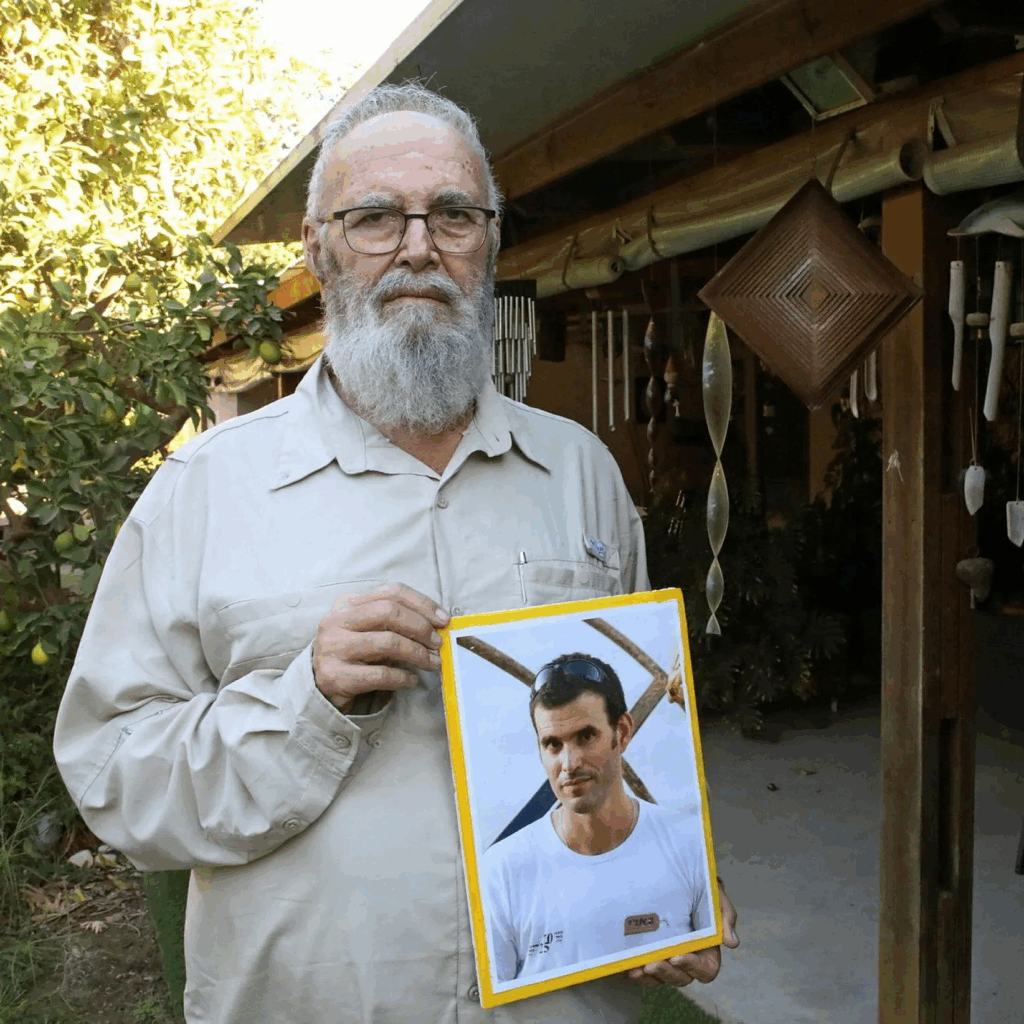

Finding Each Other

If there was one theme that echoed throughout this trip, it was that reconciliation is neither linear nor inevitable. It is fought for, often haltingly, always imperfectly. It requires truth-telling and repair. It demands that we keep trying to find each other, even when history and pain push us apart.

South Africa’s struggle is not over. Apartheid’s legacy lingers in economic disparities, the grotesque juxtaposition of high-walled mansions with corrugated tin townships, and unfulfilled promises. Yet, there are lessons here—about resilience, vision, and what it takes to keep moving toward peace, even when the road is long.

The path to reconciliation, whether in South Africa or in Israel and Palestine, is filled with uncertainty. But if there is one thing I know, it is this:

The work of peace is to keep on trying to find each other. And I am more committed than ever to doing just that.