Zeinat Awad

My name is Zeinat Awad, from Beit Ummar in the West Bank.

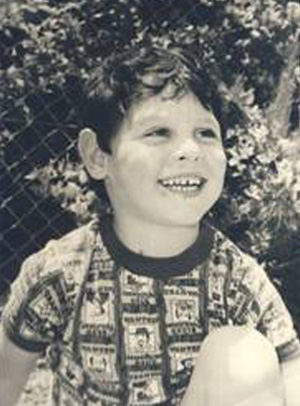

My children were born into a reality burdened by occupation, growing up witnessing daily scenes of oppression—killings, arrests, land confiscation, and the relentless expansion of settlements. My eldest son, Jaafar, was an ambitious young man, who believed that the future of his homeland could be built through education and went to law school so he could work for justice for his people. He also had a black belt in karate, and dreamed of representing Palestine in international tournaments.

One day on his way to university, he passed through a checkpoint—as usual—and his life changed forever. An Israeli soldier stopped his car, slapped him, and humiliated him in front of others. In that moment, Jaafar felt how easily a person’s dignity could be crushed, and that justice—the very thing he was studying—was absent under the occupation.

In deep frustration, a thought took shape in his mind—as he later admitted—to “teach the occupation a harsh lesson.” It was only a thought, nothing more. But before he acted upon it, the Israeli military arrested him and charged him not for an act, but for the thought itself.

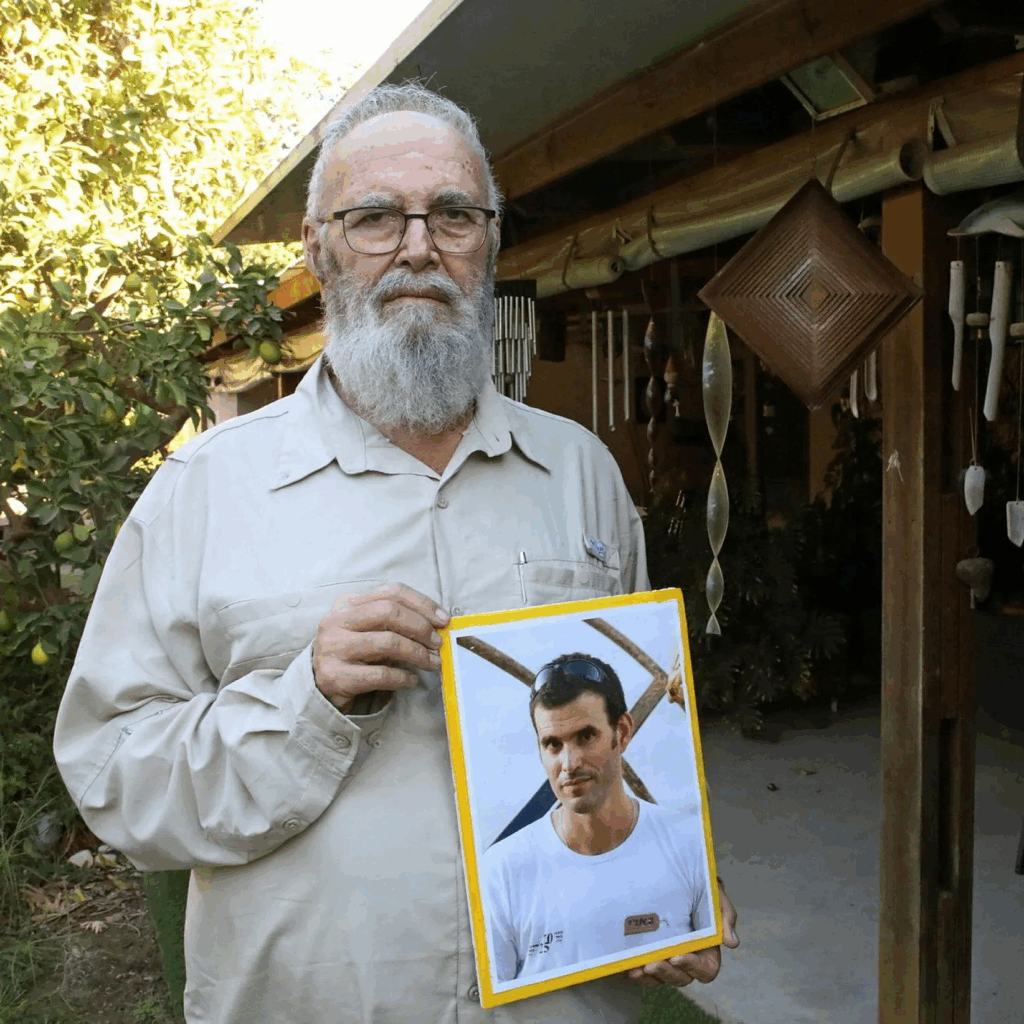

Inside prison, Jaafar suffered from multiple illnesses and in early 2015, Jaafar was released in a frail and weak condition. We took him to a doctor who told me “Your son will not live for more than three months”.

We took Jaafar on an exhausting journey through hospitals for treatments—Al Ahli, Al Makassed, Al Mutlaa, and Al Mezan hospitals —where he finally passed away on April 10, 2015.

Today I am a member of the Parents Circle, and firmly believe that pain can be transformed into a force for justice and peace. My suffering continues, as my two younger sons are currently in administrative detention, with no reason given, and the youngest is only 16 years old.

Despite my loss and pain, I believe in life and in my son’s dream of education and justice. I now carry two voices within me: one of a mother who has lost her son, and one of a woman who believes that another future is possible.